The Role of Vernacular Architecture & Urbanism in Mitigating Heat

Vernacular architecture is often appreciated for the historic aesthetic value that it presents. Preservationists and activists argue on the importance of preserving historic structure from a cultural angle: its unique character, the story that it tells, the memories people associate with a particular building. States and institutions may feel inclined to preserve such structure, to instill a national identity. To frame the nationalist state as an idea and concept much older than it is. Preservation vernacular architecture could also be argued for in economic terms. The Qatari state has begun heavily investing in heritage tourism as an alternate source of revenue. Yet, it is not often that preservation is argued for under an environmental lens.

We view the humanmade, the cultural, as something that is inherently opposed to the natural: but should that be the case? We understand and perceive the urban and urban spaces as something that is not natural. If anything, urban environments are seen as antithetical to the environment. Nature was seen as something to be conquered by humans. Nature was scary. It's home to beasts and fauna that could potentially be hazardous and poisonous. Moreover, nature was something to be exploited. It was through the exploitation of natural resources that man was able to build and create robust economies. This point draws an essential question to our understanding of urban spaces and where they stand in relation to the natural environment and requires a fundamental change in that understanding.

Dubai, UAE

Dubai has become a poster-child in the region of building with little regards to environmental context.

There is an underlying foundational issue with how urban spaces are being built and manifest themselves in the 21st century in the Persian Gulf, and the Arabian Peninsula more broadly speaking. Does it make sense for architects, engineers, and urbanists to import architectural and urban styles and building methods in a region where the very environment rejects it? Urban heat islands have been written about extensively in academia and the press, how glass towers and wide avenues of asphalt heat our cities are well documented and understood. In a region where the natural climate is already naturally hot, it is vital to mitigate the urban heat island effect as much as possible when designing our cities.

The most critical factor in giving architecture a distinct look and feel is the environment and climate. Legendary architect and scholar Hassan Fathy writes in his book Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture that "Climate, in particular, produces certain easily observed effects on architectural forms." Whether in the deserts of New Mexico or the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, architectural principles follow very similar patterns: smaller windows, flat roofs, mud bricks, and projecting wooden spouts to collect water. Despite the geographical distance and the lack of communication modes between the two regions, it is surprising to see how similar these indigenous styles of architecture genuinely are.

Pueblo de Taos, New Mexico, USA

Wadi Daw’an, Hadhramaut Governate, Yemen

The manners in which we have constructed our buildings, and by extension, our cities are mostly void of these environmental contexts. Architects and preservationists have long made an argument against the "International Style" where it is not suitable for the climate. Hassan Fathy writes on the adoption of the International Style in the tropics:

“Changing a single item in a traditional building method will not ensure an improved response to the environment or even an equally satisfactory one. Change is inevitable, and new forms and materials will be used, as has been the case throughout history. Often the convenience of modern forms and materials makes their use attractive in the short term. In the eagerness to become modern, many people in the Tropics have abandoned their traditional age-old solutions to the problems presented by the local climate and instead have adopted what is commonly labeled “international architecture,” based on the use of high-technology materials such as the reinforced-concrete frame and the glass wall. But a 3 x 3-m glass wall in a building exposed to solar radiation on a warm, clear tropical day will let in approximately 2000 kilocalories per hour. To maintain the microclimate of a building thus exposed within the human comfort zone, two tons of refrigeration capacity is required. Any architect who makes a solar furnace of his building and compensates for this by installing a huge cooling machine is approaching the problem inappropriately, and we can measure the inappropriateness of his attempted solution by the excess number of kilocalories he uselessly introduces into the building. Furthermore, the vast majority of the inhabitants of the Tropics are industrially underdeveloped and cannot afford the luxury of high-technology building materials or energy-intensive systems for cooling. Although traditional architecture is always evolving and will continue to absorb new materials and design concepts, the effects of any substitute material or form should be evaluated before it is adopted. Failure to do so can only result in the loss of the very concepts that made the traditional techniques appropriate.”

However, it is not enough to adopt these ideas in the architectural context; we must study and understand this ideology on a grander scale. The past 50 years of urban development in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula have primarily been motivated by the luxury, spectacle, and above-all: capital. It is not surprising that the lands that were stricken with the harshest levels of poverty and one of the worst qualities of life would want to free themselves from that life and adopt the new and modern. The tradition was a reminder of darker days. The people of the Persian Gulf embraced the new because it brought forth a better quality of life. Knowledge and expertise were outsourced to Europe, in the Khaleeji context, primarily to the British and Americans, who modeled our cities and capitals after their own. The automobile was embraced in the design, and wide avenues had to be built to accommodate more vehicles. Naturally, cities became covered in asphalt. Zoning codes mandated that buildings had to have sufficient parking spots for automobile drivers. Our new urban environment could only be described as an asphalt desert.

The impact asphalt has on the heat island effect is well documented. Dubai, one of the fastest developing cities in the region, has seen a 64.8% change in land cover and a 1.5 degree C rise in land surface temperature. Projects like the Blue Road on Abdullah Bin Jassim Street by Souq Waqif are certainly exciting in that aspect in mitigating this effect. But is this A) Enough? B) Actually helping? While the street has seen a decrease in temperature, it ignores the issue at large: Our urban design does not make sense in our environmental context.

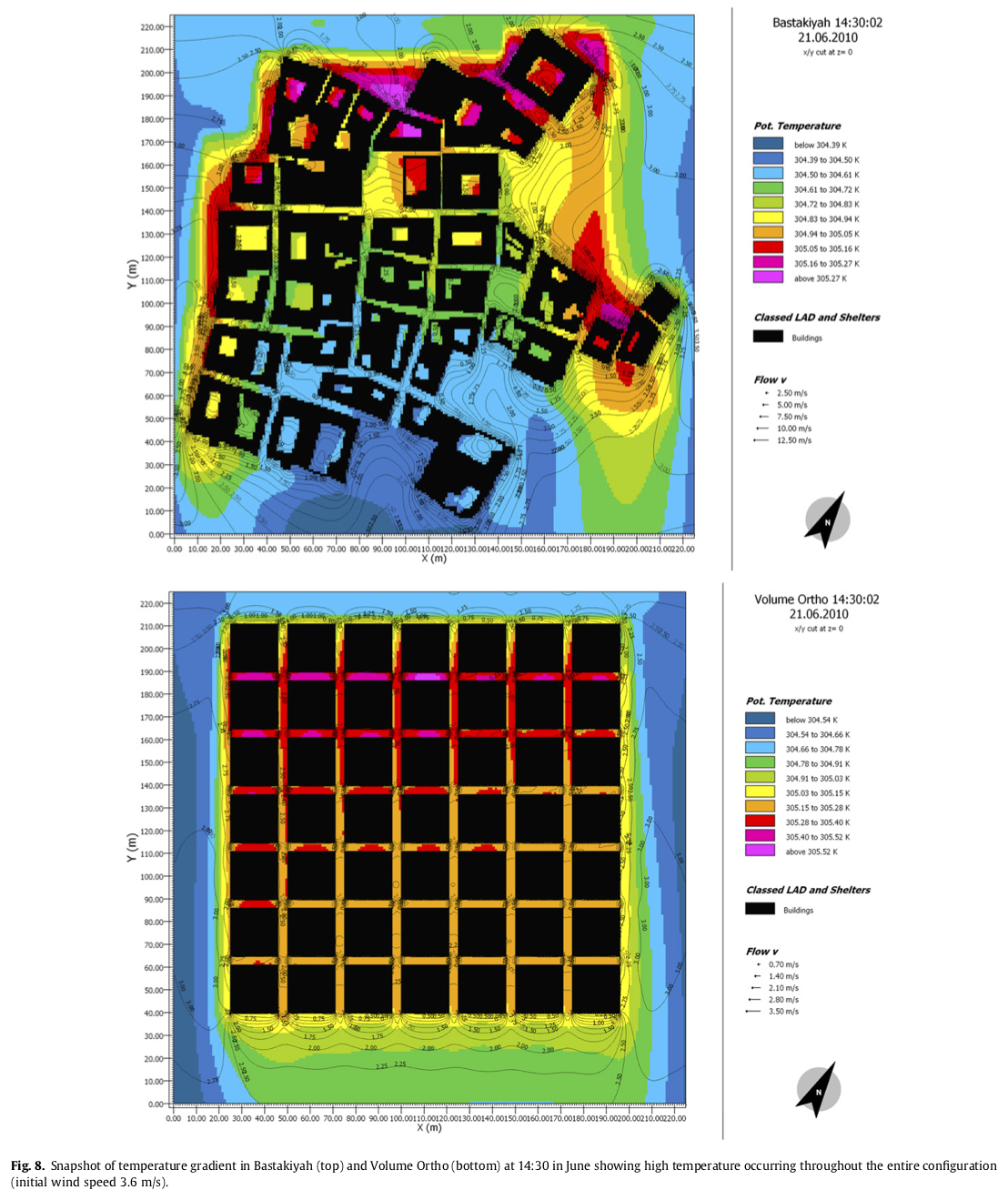

Our forefathers built verandas by mosques and commercial areas, had narrow streets that gave shade to pedestrians, and created a scale in which people felt more comfortable walking. Moreover, despite the propagation of the idea that Khaleeji Urbanism was built with little regard to proper city planning measures is a false notion. A study that compares temporal variations 'organic' and 'structured' urban configurations in Dubai shows that the "organic" historic neighborhood of Al-Bastakiyah was "cooler in summer and autumn" than the 'structured' Orthogonal and Volume Orthogonal configurations. The configuration of the streets contributed to a smoother distribution of temperature throughout the entire site by directing the wind. Street and building orientation were built in terms of wind direction. This shows that a great deal of thought went into planning the streets and sikkak in Khaleeji towns before any colonial planning practices and that the supposed 'organic' structures were far better organized and structured than the modernist principles enforced by British engineering and architectural offices. Additionally, that same study concludes that the Bastakiyah street configuration should be selected as the recommended configuration not only for its thermal behavior, but also for the other sustainability dimensions it promotes.

“This type of configuration allows for higher levels of privacy and in other instances increased social interaction. It responds best to the cultural aspect of the society and at the same time to the climatic conditions of the city.”

Snapshot of the Al-Bastakiyah Neighborhood in Dubai, UAE

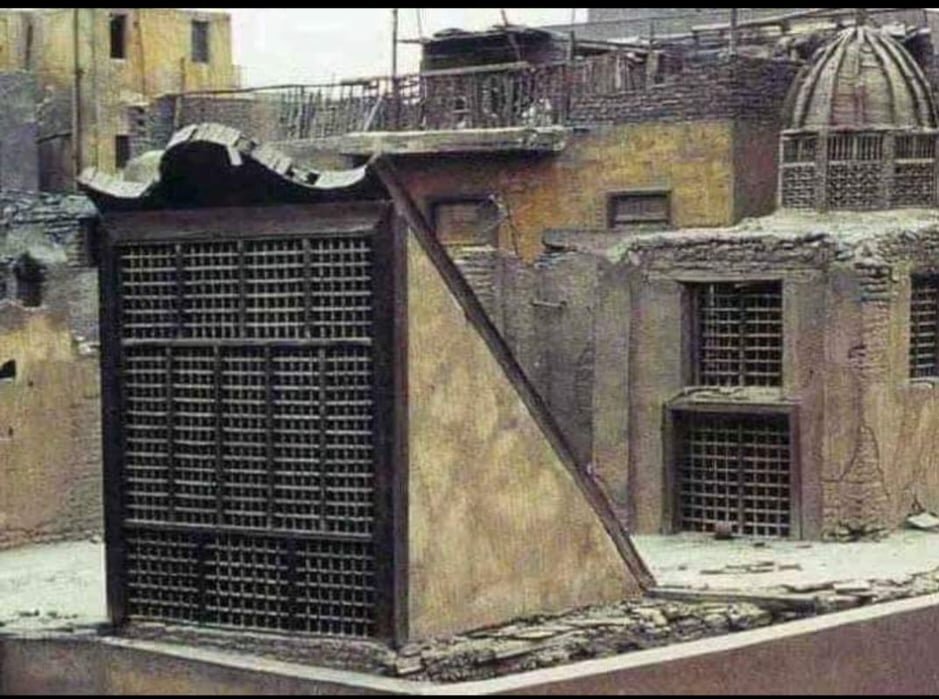

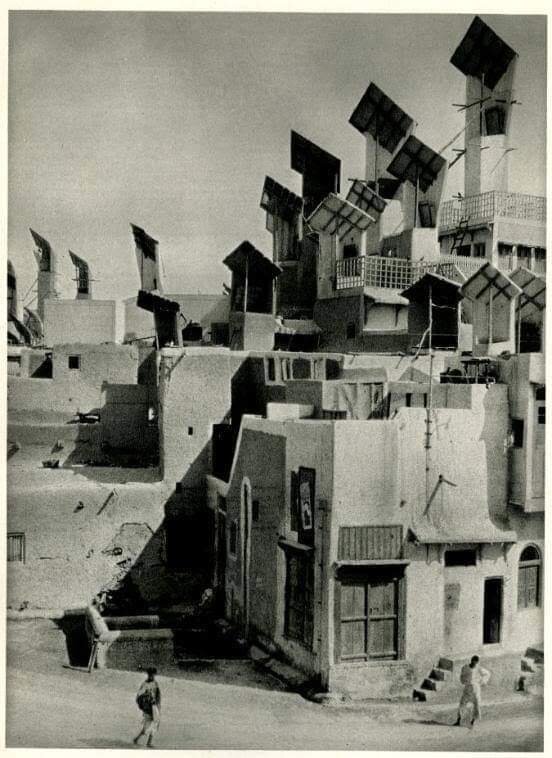

Perhaps the best example of cooling technology in the Middle Eastern context is the wind catchers or the wind towers, also called barajeel (sing. barjeel), malaqif (sing. milqaf), and badgir. Wind catchers have come in an array of styles across the Middle East and South Asia, including Egypt, the Arab States of the Persian Gulf, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan (It very common in the Sindh Province, where it was called Manghu) . A masterpiece of mechanical engineering developed thousands of years ago, architects and engineers were able to bring thermal comfort into their homes through these vertical wind channels. It is based on the principle of cold air suction from higher elevations into buildings. It acts as a natural solution developed in a pre-mechanical air conditioning era in hot desert climates. Residents of these hot climates were forced to adapt to their natural environments, and through that, they were able to innovate. The crucial underlying point here is that this technological innovation was spurred about by necessity, due to its geographic and climatic situation. Towers can vary in design, height, and depending on whether the climate of specific geography is dry or humid, the technology can vary slightly.

For thousands of years, barajeel provided natural ventilation of air that is free from pollutants and dirt due to the elevated air source. This air flows into the interior spaces of the house, such as a living room or a bedroom of sorts. Regardless of the building's orientation and its relation to the wind direction, the barajeel were still able to cool down buildings. In dryer climates, the airflow can be directed through a water source such as a fountain to increase humidity. It is astonishing today to look at these technologies, as most people today cannot fathom how to live in our environment without mechanical air conditioning, and considering how four of the ten highest countries in electricity consumption are situated in the Persian Gulf, we should consider how to reduce electricity consumption to become environmentally sustainable. Dr. Ayman Alsuliman at the University of Jordan (2014) has written on the merits of wind catchers as an environmentally friendly technology for cooling. He cites that mechanical air conditioning relies on Freon gas, the cooling agent used in most air conditioning systems, extremely harmful to the environment, while wind catchers don't. He also notes that the higher oxygen levels in the air with the guarantee of continuous ridding of CO2 and ensures higher productivity levels. The study also concludes that natural underground ventilation systems result in 60% savings in energy consumption compared to mechanical cooling. Technological innovation and mechanical cooling systems do not call for the riddance of traditional cooling methods; instead, we should embrace and innovate new technologies and build on cooling methods used in vernacular architecture.

So, what does this mean? Where do we go from here? Should we return to building houses from mud bricks and tear down our roads? Not quite. However, when designing new neighborhoods or retrofitting current suburbs in our cities, we should perhaps embrace traditional building methods and philosophies. Why turn to European expertise and philosophies in our city building when our builders had the right idea for centuries? Earlier in this article, I called for a radical change in our understanding: but these fundamental ideas are not radical. These were ideas that are tried and true, age-old and have worked for years. This idea is not at all revolutionary, it's common-sense. If it responds best to our climactic condition and the cultural elements of society, why should we not adopt it?

This article was inspired by the brilliant Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. I wholeheartedly recommend reading his books if you are at all interested in vernacular architecture. Both Architecture for the Poor and Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture, although the latter maybe hard to find.

Articles Referenced:

Alsuliman, A. (2014). Wind Catchers and Sustainable Architecture in the Arab World. Journal of Civil and Environmental Research, 6, 130–136.

Taleb, D., & Abu-Hijleh, B. (2013). Urban Heat Islands: Potential effect of organic and structured urban configurations on temperature variations in Dubai, UAE. Renewable Energy, 50, 747–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2012.07.030