Five Years In: On Planning, Power, and the Everyday City in Qatar

Most blog posts I’ve written here have had a target: to tackle urban woes and their impacts in Qatar and the region. But this time, I want to write something more reflective, what it feels like to be a practicing planner five years in. How I see the field today, what planning praxis looks like in Qatar, and what I think our national trajectory is shaping up to be.

Urbanism is a fascinating topic. I may be biased as a city planner, but I’ve always found it telling how everyone has an opinion on the built form. We all live inside the city, move through it, depend on it, so we all have a stake in how it is designed, managed, regulated, and experienced. The way we build and run our cities shapes the way we live our lives. It’s partly why some of the most influential voices in planning didn’t come from planning departments at all: Jane Jacobs (journalist and activist), Lewis Mumford (historian and cultural critic), Henri Lefebvre (philosopher and sociologist), and many others.

Doha Corniche in the Late 60s. (Source: @atiqalsulaiti on X.com)

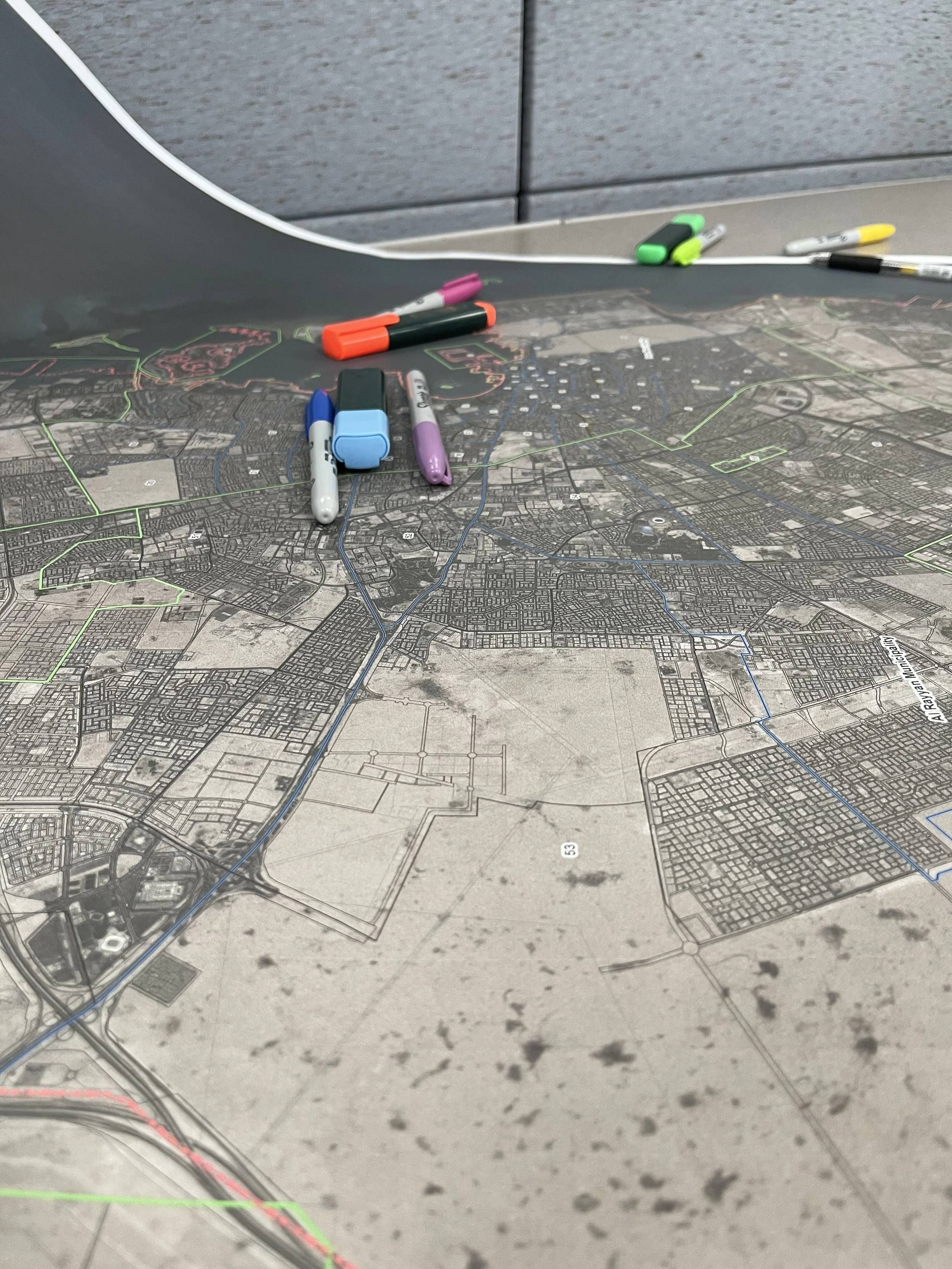

In Qatar, urban governance and planning is not a new experiment, it’s an old praxis. The State has long relied on global firms to shape Doha at different levels of planning. In 1971, a team from Llewelyn-Davies Weeks Forestier-Walker and Bor was invited to advise on the city, and they were formally contracted the following year. It was through their recommendations that an Urban Planning Department under the Ministry of Municipality was established in 1973. At a higher level, the Office of His Highness the Emir was also deeply involved in shaping the city directly, overseeing major projects, chief among them the New District of Doha (what we now know as West Bay/Al Dafna), with William L. Pereira & Associates responsible for developing and actualizing that plan. Later, in the 1980s, the Ministry would contract firms like Shankland Cox and Dar Al-Handasah to develop detailed plans for Doha’s redevelopment.

Urban Planing and Development Authority Tower, Doha, Qatar (Source: lookphotos / Stumpe, Jürgen)

Institutionally, the shape of planning governance has also shifted over time. In 2004, HH Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani (then Deputy Emir) signed the law establishing the Urban Planning & Development Authority. It remained an independent authority until 2014, when it was merged into the Ministry of Municipality to become the Ministry of Municipality & Urban Planning. Today, the sector remains under the Ministry of Municipality, especially after the separation of the Ministry of Environment.

At the same time, planning education in the country has noticeably withdrawn. The program is no longer offered at the undergraduate level, and urban planning has largely become a master’s track limited to those coming from engineering and architecture backgrounds. Scholarships dedicated to urban planning are practically non-existent, with the discipline often absorbed under a broader umbrella of “policy and planning” rather than treated as a field in its own right.

This preamble gives context to what I feel at this stage of my career, planners in Qatar are not always given their due as a profession. And that’s deeply concerning, not only as someone working in the field, but as a Qatari who cares about what our cities are becoming.

So, what is a planner in Qatar today?

It’s a question I’ve found myself returning to, sometimes out of curiosity, and sometimes out of frustration. What is the planner in the Qatari context?

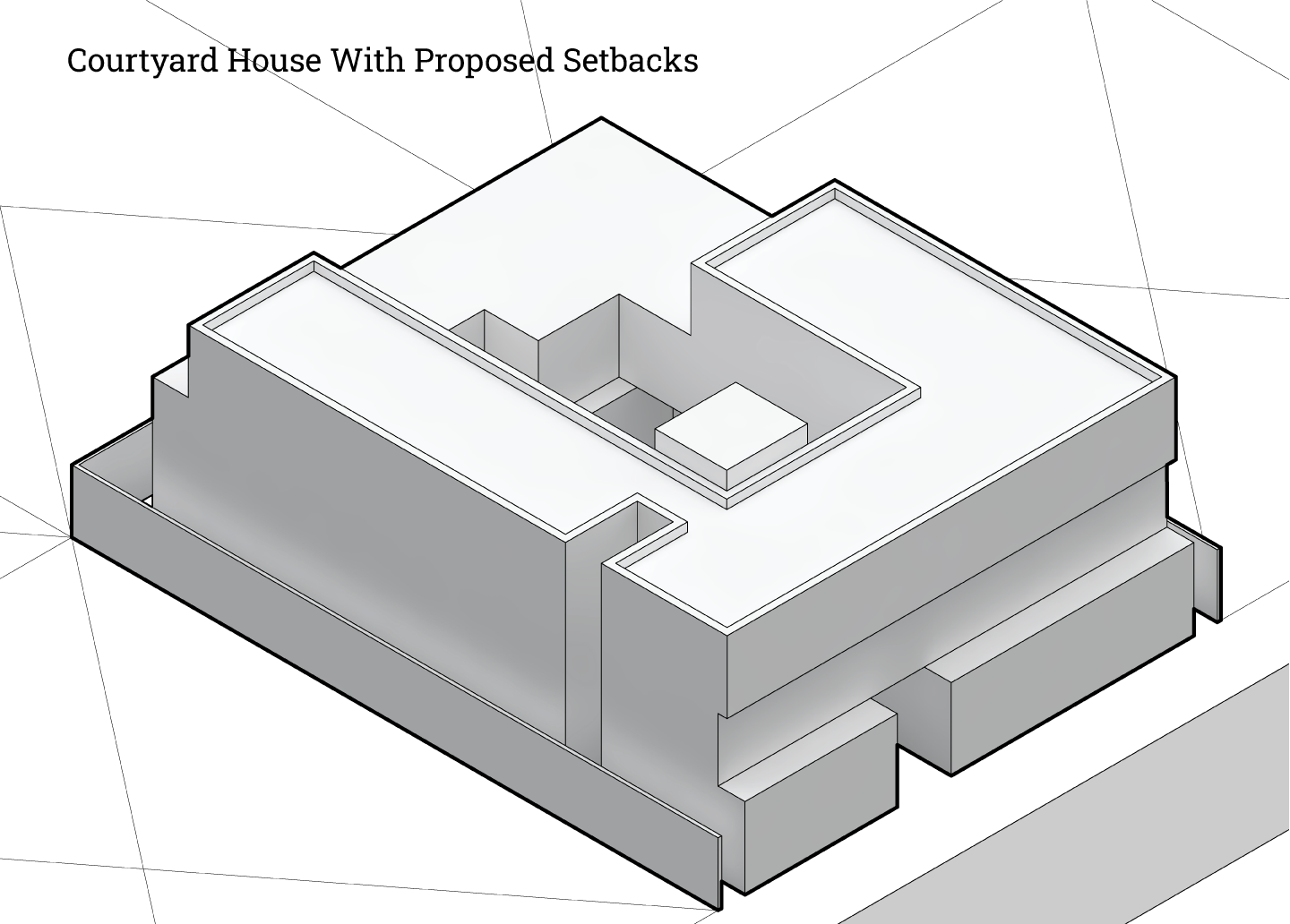

The Human Resources department tells me I’m a “policy analyst.” That the work we do isn’t technical in nature. That we operate within the confines of an office, behind a screen creating, adopting, and measuring KPIs on urban policies. Ministerial decisions, on the other hand, define the Urban Planning Department through a much broader mandate: the preparation of urban, structural, and general plans for cities, towns, rural communities, and villages; the preparation of detailed studies and projects for neighborhoods and communities; the development of planning criteria and land use regulations; and the monitoring of urban structure through field surveys.

On the ground, however, planning is often perceived as an extension of the building permit process. We process approvals for larger projects and mega-developments, and we update regulations when issues emerge during implementation. Among the general public, the Department is often understood as “the land authority”, the place where decisions about plots, zoning, and large-scale approvals are processed. Within this dynamic, I’ve often felt that the role and value of the practitioner is not well understood.

So, what is the role of the planner in Qatar today, to me?

It is far deeper than a policy analyst confined to a desk. We are obligated to conduct site visits. We conduct studies. We create codes and regulations that engineers and architects are expected to design within. And yet, the planner is often not compensated as technical staff, neither through internal HR classification, nor through national frameworks and policies governing public service roles. The irony is difficult to ignore: we are asked to shape technical outcomes, but we are never treated as technical professionals. The planner is the quiet engineer of outcomes, accountable for the city’s failures, yet rarely credited for its successes. The planner is the state’s spatial conscience, balancing growth with identity, land value with equity, and urgency with responsibility. The planner is a technical professional designing the systems of land use, mobility, density, and regulation that determine how a nation lives.

So why is the value of the planner misunderstood?

Part of it is on us.

Planners everywhere have never been great at marketing our occupation. We like to imagine ourselves as silent soldiers: doing the work quietly, avoiding the spotlight, trusting that good planning will speak for itself. In the Qatari and Khaleeji context, that media shyness can be even more pronounced. But part of it is structural. The outputs most visible to the public are subdivisions, zoning decisions, and building regulations. If that is all people see, then it is no surprise that planners are perceived as custodians of land and gatekeepers of approvals. And because much of our interaction with decision-makers is also framed through approvals and regulation updates, the image often remains the same even at higher levels.

How often have planners presented detailed neighborhood strategies to the public? How often have we spotlighted the work of the landscape architects, urban designers, and planners shaping new residential districts, and asked them to explain the design philosophy behind street networks, public space, shade, walkability, and identity? When we don’t narrate our own work, others will narrate it for us, and they will usually reduce it to whatever is most visible: permits and plots.

And then there is the deeper issue: the gap in planning education.

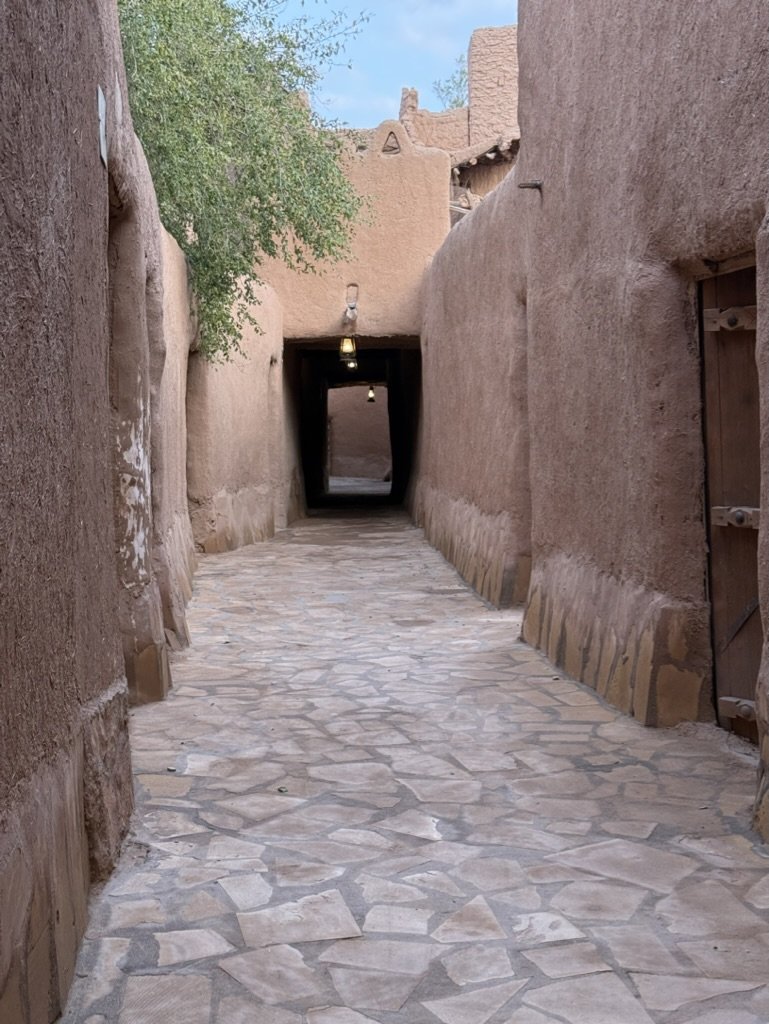

The gap in planning education has cost the State deeply, both on a technical level and strategic level. The absence of national planners rooted in local customs and traditions creates a major gap in our ability to translate international best practice into the Qatari context. Beyond that, many decision-makers lack the technical depth needed to interrogate recommendations: to test whether a proposed planning direction makes sense, and whether the evidence behind it is reliable. This has produced an overreliance on imported planning knowledge and practitioners to fill the technical gap. But even when that “band-aid” holds, the higher-level gap remains: a shortage of local planning leadership capable of steering the country’s urban trajectory with confidence, context, and accountability.

Five years in, I don’t feel like I have all the answers but I do feel like I’ve earned a few convictions. They came from site visits in the heat, from meetings that stretched longer than they should have, from regulations that looked simple on paper and complicated in real life, and from watching how small decisions echo across an entire neighborhood. Here are five lessons I’ve learned, and lessons passed down to me from my seniors at the department when I first started:

Lesson 1: Be inquisitive, beyond curiosity!

(Source: pexels / Leeloo The First)

And by that I mean ask questions relentlessly, and don’t stop at what the process is. Ask why it exists in the first place. Why does a workflow function the way it does? Why were certain codes written this way? Under what conditions were they designed, and do those conditions still exist today? Why did certain projects receive special approvals, and what precedent did that set? That kind of inquiry is how you move from simply enforcing inherited rules to actually improving them. If you want to build better regulations, you first have to understand the logic and the history behind the ones you’re enforcing.

Lesson 2: Do not give up a single square inch of park space.

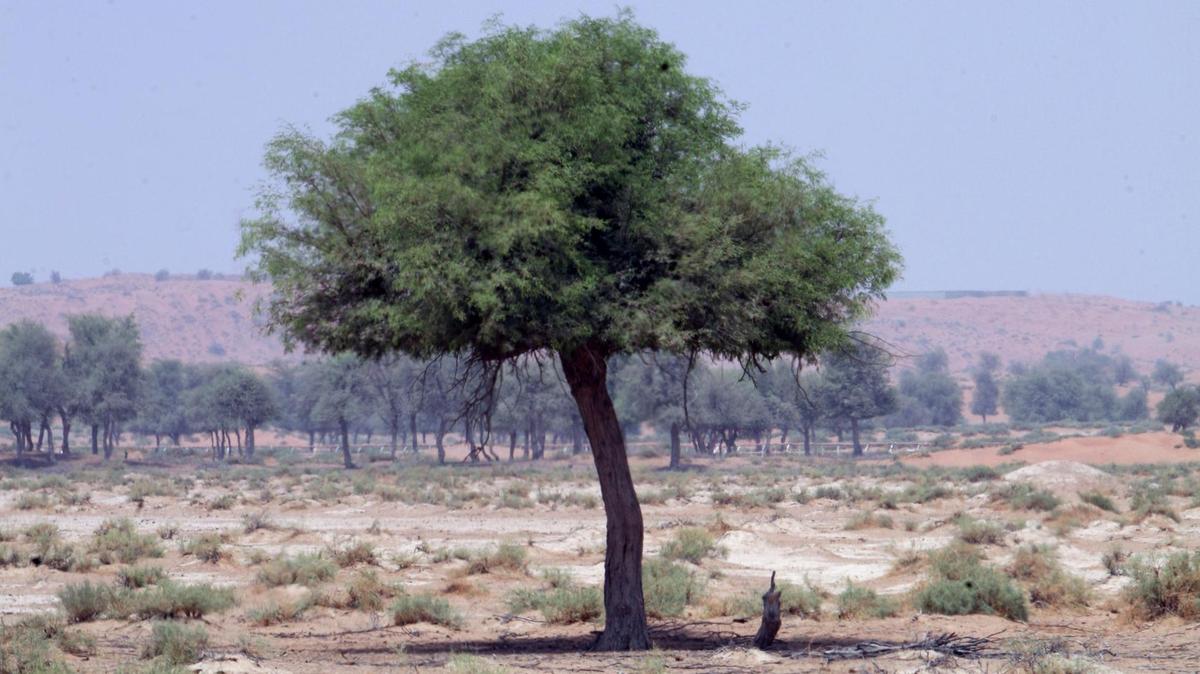

We are often too quick to surrender park space for two reasons: it produces no immediate economic return, and in Qatar it costs real money to build and maintain. But parks are not “leftover land.” They are public infrastructure. They’re where children learn the city. Where neighbors become a community. Where a district gets its breathing room. And in a hot climate, shade, trees, and well-designed public space aren’t aesthetic luxuries, they’re health and resilience measures that reduce heat stress and make everyday walking possible. A good park also pays back quietly over time: it supports mental wellbeing, offers free recreation across income levels, strengthens neighborhood identity, and creates places to gather that aren’t gated, commercial, or exclusive.

Lesson 3: Build your network within the bureaucracy.

Planning is intersectional by nature. Every serious planning decision touches multiple sectors: transport, environment, heritage, utilities, housing, public health, tourism, and more. To understand projects properly, you need data and perspective from all sides, and you will not always have direct access to either. A strong network across entities (and across departments within your own) is not a “nice-to-have.” It is part of the job. Know the direction different institutions are taking. Understand how they see their own mandates, projects, and constraints. Learn the language of the heritage and museums sector, the environmental sector, infrastructure agencies, and others and look for ways to connect them. Synergy isn’t accidental; it has to be built.

Lesson 4: Stay engaged!

Keep learning. Stay current with planning literature. Write articles, reflections, even short notes that force you to clarify your thinking. Give talks. Attend public forums (or whatever the municipal equivalent is). Go to conferences. Spend time with academics. Travel to other cities and observe with intention. It is dangerously easy, in government work, to become a “regulation bot”, someone who enforces rules inherited from another era without questioning whether they still serve the city. Staying engaged is how you remain a professional, not just a processor.

And finally, the most important lesson I’ve learned…

Lesson 5: Do not compromise on best practice!

I’ve seen planners and designers, time and time again, give up on arguing for best practice, not because they don’t believe in it, but because the process is exhausting. And it is exhausting. But as a trained planner, you have a responsibility to uphold a professional standard. Some decisions will always be political. That’s reality. But it is not your role to predict what decision-makers will choose and then dilute your technical recommendation in advance. Write the recommendation as it should be, grounded in sound planning principles and evidence. If leadership chooses a different path for political reasons, let that be a decision made on its own terms, with its own accountability. Your role then becomes to mitigate negative consequences as much as possible, without rewriting “best practice” into something unrecognizable.

So where does that leave us?

If we keep treating planning as a back-office function, something adjacent to permits and paperwork, we will keep getting cities that behave like paperwork: efficient on paper, expensive in reality, and emotionally thin. The profession cannot mature if it is unclear, undervalued, and under-trained. And the country cannot rely forever on imported expertise to supply judgment it has not cultivated locally.

We need to invest again in planning education, professional recognition, and public literacy because these are not nice-to-haves; they are the foundations of urban quality of life.

I don’t write this as someone who has figured it out, I write it as someone who has finally understood what the job actually asks of you. In Qatar, the planner lives between definitions: between what the org chart says we are, what the public thinks we do, and what the city truly demands from us. And that gap matters, because cities don’t absorb ambiguity politely; they absorb it through heat, traffic, isolation, fragmented neighborhoods, and public spaces that never become public.

But I’m not pessimistic. I’ve seen how much can change when a planner is empowered to ask “why,” when public space is treated as non-negotiable infrastructure, when networks across government actually function, when professionals stay engaged with knowledge rather than only process, and when best practice is defended with a straight back, even if the final decision goes elsewhere. These lessons are small on paper, but they accumulate. They shape the quality of neighborhoods. They shape trust in institutions. They shape whether our cities feel like places we belong to, rather than projects we pass through.

If planning education has withdrawn, then those of us practicing today carry a heavier responsibility: to be both practitioners and translators, both technicians and advocates, both public servants and students of the city.

My hope is that, as a country, we start treating planning not as paperwork and approvals, but as nation-building, expressed through streets, parks, codes, and the everyday life they make possible. And if I’ve learned anything in these five years, it’s this: the city will outlive our meetings, our memos, and our job titles. What remains is what we chose to protect, and what we chose to compromise.

The Amiri Diwan, Doha, Qatar. (Source: Myself)